A primary function of government is the protection of citizens, as well as of private and public property. Laws and their enforcement play a major part in this work, of course. In recent decades, however, we have become increasingly aware of the true cost of crime, not only to the victims and the perpetrators, but to the community as well such as the ongoing expense, for example, of building and maintaining prisons; the care and feeding of inmates—sometimes for years; recidivism; and, not to be forgotten, the damage to families, both the victim’s and the perpetrator’s.

This is why the traditional bulwarks of law and enforcement have been joined in recent years by a third area of governmental involvement: prevention. It can take many forms; it requires the cooperation of city residents; it involves recognizing patterns of activity that can lead to crime and defusing volatile situations; and, if done right, it pays off. Indeed, preventative action is now seen as the most effective way of reducing the need for law enforcement officers to intervene as enforcers, beginning the whole costly (and sometimes dangerous) process of arrest, prosecution and incarceration.

Prevention Costs Less than Enforcement: Just as a number of factors can contribute to criminal activity, so there are several preventive avenues that can lead to the reduction of and decreased potential for criminal activity. The Connecting Cleveland Plan outlines some specific ways in which residents, and Law enforcement personnel, the City and other stakeholders of our neighborhoods can begin the process of reducing the likelihood of crime in their communities. The more effort and energy we put into defusing criminal activity today, the fewer dollars we will need to spend on enforcing the Law and punishing criminals tomorrow.

Some Lessons Learned: In most major conflicts throughout the world, battles are fought on two fronts. There is the physical war, which utilizes hand-to-hand combat, weapons and technology. And then there is the other war, which does not entail weapons and bloodshed. Here the goal is to create human connections, getting the people who pose the threat to see that their own best long-term interests lay in cooperation and constructive activity.

The sad fact is, there is a war going on in many of our neighborhoods between police, gangs and other at-risk youth who believe their best interests are served by activities that violate the Law and endanger themselves and others. Simply writing these youths off as a menace to society and a segment of the population that should be rounded up and locked away somewhere is an easy response; but that is to put the whole burden on the police and the courts, which, as we have seen, is no longer a realistic or affordable alternative. It also ignores the human cost, and fosters a polarized, cynical community in which each side thinks only of itself.

Replacing Alienation with a Sense of Community: If we approach our antagonists, in the work place or the streets, thinking only of the outcome that will meet our needs, nothing will change. Ostracize them, lock them up; they will be back, and others will take their place. The only real way to interrupt the cycle, as the great wisdom traditions of the world have understood, is to want a good outcome for one’s antagonist too (a win win situation). That requires listening to her needs, his anger, their frustrations, and then working together to craft an outcome that will answer both your needs. This is after all the whole principal of community, and the only approach that addresses the problem at its roots and therefore brings with it the possibility of progress. If nations have not yet learned this lesson, successful married couples, skilled organizational facilitators, and a growing number of parents, have; and a growing body of evidence shows it works.

Thoughtful initiatives addressing the dynamic that exists between police and neighborhood youth are currently under way at the Police Student Academy and PAL (Police Athletic League); but the realities on the street are sobering. The social and economic conditions—and negative influences—that impact our young people and adolescents have become much more challenging than at any time in Cleveland’s history.

There is no simple solution to these problems.

It is going to take every segment of the community—neighbors, churches, businesses, social services, health care and educational institutions, civic organizations, government, the media, law enforcement officers and the courts—playing its respective role with a new thoughtfulness and determination, as part of a coordinated strategy, to make real change in the lives of youths and thus to have a positive impact on criminal activity. Other cities throughout the country are taking bold steps to deal with at-risk youth and gang violence. To learn more about what they are doing, and the thinking behind it, click on Best Practices.

Somebody’s Big Brothers or Sisters: The key is to see the youthful offender not simply as a hoodlum or gang member, but as somebody’s son or daughter, somebody’s big brother or little sister. Many of us can remember a time when you could ask a child what he or she wanted to be when they grew up, and the reply would come quickly and easily: a doctor, a lawyer, a fireman, a nurse, a police officer. Nor was it an accident that these particular walks of life were so frequently cited: All were seen as everyday heroes who enjoyed the respect and admiration of the community, particularly its youth.

Acting in such a way as to rekindle that respect, trust and admiration is the only way to head off a grim future that is otherwise inevitable. It is here, in the battle for these young people’s hearts and minds, that the real war on crime needs to be waged. Ironically, such an effort will not cost anything like the millions of dollars required to build and operate more prisons, mete out punishment and repair the social and economic toll of anti-social or violent behavior, only the willingness of dedicated officers, residents and others to take the time to connect and communicate with our young people. Law enforcement officers know, better than anyone, that today’s youths will become either tomorrow’s leaders or productive citizens or tomorrow’s criminals. Opportunities exist for law enforcement officers to reconnect with the youth in our neighborhoods. This kind of positive interaction must be encouraged and facilitated.

One place this is happening is the Student Police Academy, a Police-initiated collaboration with the Cleveland Municipal School District (CMSD) that allows students to become Junior Police Cadets as a way of building a positive image of police among city youth and stimulating interest in law enforcement.

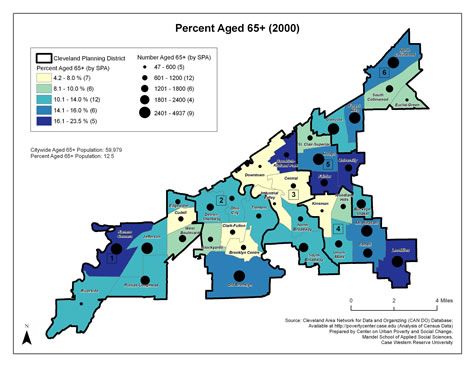

“Crime Colleges” for seniors: Each year, hundreds of seniors become victims of crimes either physical or financial. Estimates from the National Center on Elder Abuse (NCEA) show an increase of 150% in reported cases of elder abuse nationwide since 1986. In 1998, in response to the growing awareness of crimes against seniors, Kentucky Attorney General Ben Chandler developed a successful initiative to educate seniors about the crimes typically perpetrated against them, teach them how to protect themselves, and how to report illegal activities. The State of Kentucky created a senior advisory council consisting of 20 individuals drawn from various state and local agencies.

What makes Kentucky’s approach unique is that it has established something called “Senior Crime Colleges”. These are seminars, held in places like nursing homes or malls or at church gatherings or community events, at which seniors learn about crime from state and local law enforcement officials and experts in deceptive financial dealings. These “Crime Colleges” are operated by the Office of Senior Protection, which, though modestly staffed, has proven effective in bringing together an impressive array of expertise--including State law enforcement, consumer, and financial experts—to focus on crimes against seniors.

Cleveland could offer a similar program by utilizing the resources of the City’s Department of Aging and its Consumer Affairs Division. This would be especially helpful in neighborhoods with a large concentration of persons over the age of 65 who are vulnerable to criminal activity.

Figure 1: Areas where large concentrations of seniors reside can make good target areas for programs that increases safety awareness (click to enlarge image)

Engaging the Community: Although the education and training of modern-day police officers, along with higher salary, has helped to unravel the tangled web of political and personal corruption associated with the unsophisticated and underpaid beat cop of earlier eras, it has also become increasingly clear that combating contemporary crime requires a different approach. The police must always maintain their ability to rush to a crime-in-progress, of course; but new research shows that only one in three crimes is ever reported; and only two in five violent crimes; and that “crimes-in-progress” now typically constitute less than 5% of all calls for police service.

The irony of these statistics is that, while citizens still witness the committing of many crimes, they are simply not reporting them—a phenomenon that was dramatically symbolized by New York’s infamous Kitty Genovese case, when neighbors watched from their windows while a woman was slaughtered, but never called the police—either because they don’t want to "get involved" or because they see the police as strangers and community outsiders as likely to turn on them. (One Cleveland resident explained why he hadn’t reported numerous drug-related incidents on his street: “You call in the cops, and pretty soon they’re poking around into all kinds of things, like [building] code violations or somebody who’s operating a day care center in their home without a license.”

As a society, we have also become more aware of the cycle of violence spawned by the “hidden crimes” of child abuse and domestic violence, and the part the abuse of illegal, and legal, substances plays in the crime and violence that plague the community.

For these additional reasons, law enforcement in communities around the U.S. (see sidebar) is increasingly taking the form of preventative, “grassroots” activities. Beginning to see policing, in Cleveland, as involving a heavy component of planning in Cleveland will allow neighborhood communities to take a “proactive” approach to crime control—by instilling in residents a sense of their responsibility as the community’s first line of defense. A bottom-up approach to crime containment can only occur if police, prosecutors, residents and other stakeholders are working in collaboration.

Addressing, Not Just Relocating, Problems: All too often, a neighborhood’s “crime problem” is not really solved but only relocated to another part of the city. When criminal activity declines in one area, it always seems to rise somewhere else: Bust five drug dealers at East 99 th & St Clair, and the illegal drug trade increases proportionately a few blocks away. The result is that the demands on limited law enforcement personnel are never reduced significantly just scattered. For professionals who realize that a neighborhood police presence, for maximum effectiveness, has to be “constant, not sporadic” and that order must be created, not simply “maintained”, this is a frustrating situation.

The result is that success tends to be measured in number of arrests rather than, as it should be, in fewer incidences of criminal activity. And when the statistics show that certain problems have actually been reduced in a neighborhood, instead of continuing to support the activities that contributed to the decline, the funding for those programs is frequently cut back or withdrawn, so that the problem reemerges.

The take-home lesson here, if we are willing to learn it, is that we must continue to

- Train and deploy specialized units with the professional skills to defuse situations that could foster violence or other criminal activities.

- Expand the scope of existing police services in our neighborhoods to include beat cops, police mini-stations, and auxiliary police.

- Foster and support neighborhood community crime councils.

- Develop a much-needed pool of funding for the personnel and advertisements needed to improve police-community relations and counter the perception that certain areas are unsafe—which can keep people (and potential new residents) away, creating a self-fulfilling situation.

A sustained commitment to these measures is critical for the successful functioning of the Division of Police in Cleveland.

The Role of Developers and Design : A comprehensive, coordinated effort is the best approach to eliminating conditions that contribute to crime and fear. That means that decisions, in other apparently unrelated sectors of activity, that impact or perpetuate those conditions or the ability of the community to mediate them must be made with the larger interests and aspirations of the community—and the problems that hold it back—in mind. Choices made in the related areas of land use and development, for example.

Whether they are aware of it or not, planners and architects can play a powerful role in the reduction and the prevention of crime, for it is they who determine how well and to what extent an environment will serve legitimate users. Cities throughout the country are enjoying the benefits of having supported programs that approach the physical environment with a view to the reduction of crime. But many planners and designers are only now beginning to appreciate the responsibility that comes with their jobs, which includes the obligation to protect the general health, safety and welfare of the citizenry, and adopting standards by which urban design can be regulated to reduce the likelihood of criminal activity.

Urban planning and design techniques that facilitate the prevention of crime and a sense of security are now being utilized by progressive cities that are serious about crime reduction. The principle of Natural Surveillance—creating open spaces where visibility is maximized—has been shown to impact crime. Other commonly used techniques include Territorial Reinforcement and Natural Access Control, the use of fences, shrubs and other aesthetically pleasing elements to send a keep-out message to would-be intruders. Creating opportunities for urban planners and designers, community groups and police to understand how the physical environment can support the general welfare of a community should therefore be a priority for Cleveland.

Rethinking the Way We Address Juvenile Crime: A well-known African proverb says that it takes an entire village to raise a child. In our society, that means all the players in the community. No sector stands apart; rather, each has its part to play. It is time the criminal justice system began using both the stick and the carrot to keep youngsters on the right track. If only because of the expense, we must begin to treat jail and prison space as a precious resource that should not be squandered when other solutions would not only cost less, but work better.

Imagining a fresh approach to any community problem involves first stepping back and taking in the “big picture”. Youthful street-corner drug dealing for example, does not occur in a vacuum. It is connected to other problems in the life of a neighborhood: everything from prostitution and robberies, crack babies, to buildings defaced with graffiti, the prophetic “handwriting on the wall” that are often the first sign that a neighborhood is on its way down. They act like a magnet for drug and other crimes. The ability of the neighborhood to create legitimate jobs, prosperity, and opportunities for advancement that its residents deserve is diminished by the moment when such symbols of disrespect begin to accumulate.

Indeed, the frequency with which phrases like “dissing” somebody—and its opposite, “showing respect”—are invoked by disaffected urban youth suggests a deeply-held value that might be appealed to and built upon through strategically designed programs. What if these angry youngsters, instead of being isolated and further alienated, were engaged in constructive activities that allowed them to see the destructive consequences of disrespecting the rights of others to a decent life and nurturing environment—and to experience the respect of the community for their positive contributions to the those things—through, for example, the creation of. a credible program of restorative community service.

Young offenders might be organized into squads whose job it is to eradicate graffiti within 24 hours after it appears, under the close supervision of the Community Policing Officer and neighborhood groups. While helping to undo some of the damage to the community’s prospects that drug dealing contributes, such a program would also provide these often fatherless (or alienated) youths with the chance to interact with healthy role models and to get to know police officers in less threatening, indeed constructive, circumstances. The officers, in turn, would have the opportunity to get to know these kids, learning firsthand which ones just need a pat on the back and which need keeping an eye on.

There might even be a rationale for paying the kids for their work. Heretical as this suggestion might seem at first blush, consider: Such an arrangement would enable these youngsters to experience—many for the first time in their lives—the satisfaction of earning a day’s pay for an honest day’s work; and it would still be cheaper than incarceration.

Community-Based Problem Solving: Imagine for a moment the potential energy for good—indeed, the multiplier effect of the synergies thus created—that could be harnessed by assembling a community-based problem-solving team composed of police, prosecutors, judges, probation and parole officers, community residents, school and church leaders, and an ever-shifting and expanding roster of other community leaders who have experience (or connections) to contribute. Put a hospital administrator on the team, for example, and creative solutions to youthful drug dealing might have young offenders working at the hospital on those horrific weekend nights when drug violence escalates. Consider the impact on these impressionable boys and girls of having to take care of crack babies.

Like the once not-yet-tried concept of community policing, a community criminaljustice system would directly involve the community as partners in identifying and prioritizing problems; moreover, it would enlist the help of all the community’s sectors in creating imaginative solutions.

To begin with, there needs to be a public debate about how we think about crime and its prevention in this city, and what our priorities should be as we craft our response to this deepening problem. Taxpayers are beginning to see that, as a result of mandatory sentencing, they are paying out millions of dollars to build new prison cells to keep relatively low-level drug “mules” behind bars for a decade or more. What taxpayers may not yet grasp is the impact this policy has on what some would suggest ought to be higher priorities: With prisons under pressure to make space for the hapless pawns of the lucrative drug trade, third-time felony rapists typically serve only about seven years these days before they are back on the street.

Is this really what the community wants? How do we bring city residents into discussions about the real trade-offs and priorities involved? What must change to enable the average citizen to take his or her place at the table when decisions are made about the best use of the finite number of jail and prison beds available?

Community policing could serve as a model for imagining our way to a fully realized system of community criminal justice. By the same token, the history of the struggle to implement community policing provides a cautionary tale. The first obstacle that must be overcome is denial—the refusal of many citizens and officials to accept that the failures of the existing system demand more than minor reforms. Another is the delusion, once having set a new mechanism in place, that the job can be done with insufficient resources. In Cleveland, for example, the limited number of community policing officers works against their ability to be effective. Our commitment to such promising strategies needs to match the level of concern we share about the problems they address—and the potential payoff in tax revenue and lives saved, to say nothing of the future viability of our neighborhoods.

Needed: A Plan That Acknowledges Everyone’s Concerns: Bringing neighborhood residents, the judiciary system and other sectors of community life together around a new strategy—and set of priorities—for addressing crime, particularly as it involves the young, requires nothing less than a new way of thinking about these problems. For devising a strategy that will achieve results that best serve the community over the long run is only one of the challenges Cleveland faces; the other is crafting a plan that speaks meaningfully to many concerns and very different points of view.

Law makers, judges, police, neighbors, merchants, educators, religious leaders, corporate decision makers, those marketing the city to prospective home buyers and new businesses, victims, older citizens, alienated youngsters, parents, younger brothers and sisters—each of these group sees youthful crime in a different way, in a different context, and with its own set of priorities. A plan that does not acknowledge—and address—the reality each of these is dealing with will never satisfy all of the players. Therefore, a way must be found to integrate all of their perspectives, and all of their concerns, into one plan.

Drawing On Cleveland’s Unique Resources: Fortunately, Cleveland has resources in this regard that are rare if not unique in the nation. Cleveland State University is the recognized authority in the region on Diversity Management, the art of dealing with differences in the course of team building, in which CSU offers training workshops, advanced courses and a master’s degree. Faculty at the Weatherhead School of Management at Case Western Reserve University have been in the forefront of the development of Appreciative Inquiry as a method for developing more effective social and organizational systems addressing key concerns both here and on the international stage. The Gestalt Institute of Cleveland (GIC) is internationally renowned for its faculty expertise and training programs in a revolutionary approach to bridging the gap between the different “realities” of seemingly incompatible perspectives.

Of special relevance where the challenges of crafting a new approach to youth crime is concerned is the Institute’s groundbreaking work in the new field known as Integral Development (see sidebar), a seminal breakthrough in the facilitation of organizational and societal change. At its core is the powerful conceptual system called Spiral Dynamics, which played a crucial role in the peaceful transition of South Africa from apartheid to democracy (see Beck & Linscott, The Crucible: Forging South Africa’s Future, New Paradigm Press, 1991).

Of particular value to social workers, primary and secondary school teachers, juvenile court judges and other officials, and law enforcement personnel would be the GIC course that focuses on working with children and adolescents, which teaches professionals how to recognize the signs of fundamental problems, including post-traumatic stress, in the way children move and hold their bodies; and teaches ways of interacting with, and guiding, them that acknowledge their realities, build a relationship of trust, and support progress toward maturity and self respect.

Back to top

Next Page:Safety:Trends |